Overview

- Summary

- What are some useful benchmarks for this?

- How are expected missing transactions chosen to immediately forward?

- How does the Fast Relay Network factor into this?

- Does this scale Bitcoin?

- Who benefits from compact blocks?

- What is the timeline on coding, testing, reviewing and deploying compact block propagation?

- How can this be adapted for even faster p2p relay?

- Is this idea new?

- Further reading resources

Compact block relay, BIP152, is a method of reducing the amount of bandwidth used to propagate new blocks to full nodes.

Summary

Using simple techniques it is possible to reduce the amount of bandwidth necessary to propagate new blocks to full nodes when they already share much of the same mempool contents. Peers send compact block “sketches” to receiving peers. These sketches include the following information:

- The 80-byte header of the new block

- Shortened transaction identifiers (txids), that are designed to prevent Denial-of-Service (DoS) attacks

- Some full transactions which the sending peer predicts the receiving peer doesn’t have yet

The receiving peer then tries to reconstruct the entire block using the received information and the transactions already in its memory pool. If it is still missing any transactions, it will request those from the transmitting peer.

The advantage of this approach is that transactions only need to be sent once in the best case—when they are originally broadcast—providing a large reduction in overall bandwidth.

In addition, the compact block relay proposal also provides a second mode of operation (called high bandwidth mode) where the receiving node asks a few of its peers to send new blocks directly without asking for permission first, which may increase bandwidth (because two peers may try sending the same block at the same time) but which further reduces the amount of time it takes blocks to arrive (latency) on high-bandwidth connections.

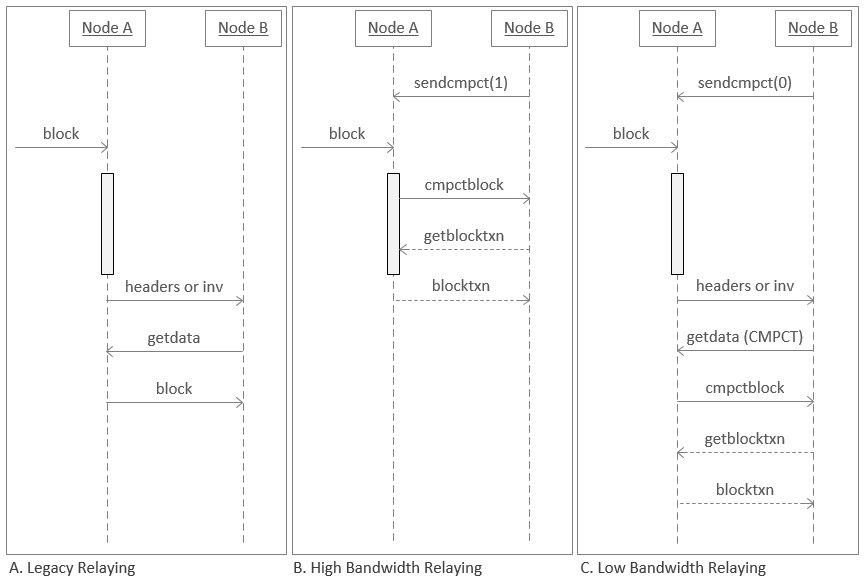

The diagram below shows the way nodes currently send blocks compared to compact block relay’s two operating modes. The grey box on node A’s timeline represents the period in which it is performing validation.

-

In Legacy Relaying, a block is validated (the grey bar) by Node A, who then sends an

invmessage to Node B requesting permission to send the block. Node B replies with a request (getdata) for the block and Node A sends it. -

In High Bandwidth Relaying, Node B uses

sendcmpt(1)(send compact) to tell Node A that it wants to receive blocks as soon as possible. When a new block arrives, Node A performs some basic validation (such as validating the block header) and then automatically begins sending the header, shortened txids, and predicted missing transaction (as described above) to Node B. Node B attempts to reconstruct the block and requests any transactions it is still missing (getblocktxn), which Node A sends (blocktxn). In the background, both nodes complete their full validation of the block before adding it to their local copies of the blockchain, maintaining the same full node security as before. -

In Low Bandwidth Relaying, Node B uses

sendcmpt(0)to tell Node A that it wants to minimize bandwidth usage as much as possible. When a new block arrives, Node A fully validates it (so it doesn’t relay any invalid blocks). Then it asks Node B whether it wants the block (inv) so that if Node B has already received the block from another peer, it can avoid downloading it again. If Node B does want the block, it asks for it in compact mode (getdata(CMPCT)) and Node A sends the header, short txids, and predicted missing transactions. Node B attempts to reconstruct the block, requests any transactions it is still missing, and Node A sends those transactions. Node B then fully validates the block normally.

What are some useful benchmarks for this?

An average full 1MB block announcement can be reconstructed by the receiving node with a block sketch of 9KB, plus overhead for each transaction in the block that is not in the receiving node’s mempool. The largest block sketches seen top out at a few bytes north of 20KB.

When running live experiments in ‘high bandwidth’ mode and having nodes prefill up to 6 transactions, we can expect to see well over 90% of blocks propagate immediately without needing to request any missing transactions. Even without prefilling any transactions except for the coinbase, experiments show we can see well north of 60% of blocks propagate immediately, the rest requiring a full additional network round trip.

Since the difference between mempools and blocks for warmed up nodes is rarely more than 6 transactions, this means that compact block relay achieves a dramatic reduction in required peak bandwidth.

How are expected missing transactions chosen to immediately forward?

To reduce the number of things that need to be reviewed in the initial implementation, only the coinbase transaction will be pre-emptively sent.

However, in the described experiments, the sending node used a simple formula to choose which transactions to send: when Node A received a block, it checked to see which transactions were in the block but not in its mempool; those were the transactions it predicted that its peer didn’t have. The reasoning is that (without additional information) the transactions you didn’t know about are probably also the transactions your peers don’t know about. With this basic heuristic, a large improvement was seen, illustrating that many times the simplest solutions are the best.

How does the Fast Relay Network factor into this?

The Fast Relay Network (FRN) consists of two pieces:

-

The curated set of nodes currently in the Fast Relay Network

-

The Fast Block Relay Protocol (FBRP)

The set of curated nodes in the FRN have been carefully chosen with minimal relay over the globe as the number one priority. Failure of these nodes would result in a significant increase of wasted hashpower and potential further centralization of mining. A large majority of mining hashpower today connects to this network.

The original FBRP is how the participating nodes communicate block information to each other. Nodes keep track of what transactions they send to each other, and relay block differentials based off of this knowledge. This protocol is nearly optimal for one-to-one server-client communication of new blocks. More recently, a UDP and Forward Error Correction (FEC) based protocol, named RN-NextGeneration, has been deployed for testing and use by miners. These protocols however require a not-well connected relay topology and are more brittle than a more general p2p network. Improvements at the protocol level using compact blocks will shrink the performance gap between the curated network of nodes and the p2p network in general. The increased robustness of the p2p network and block propagation speed at large will play a role in how the network develops in the future.

Does this scale Bitcoin?

This feature is intended to save peak block bandwidth for nodes, reducing bandwidth spikes which can degrade end-user internet experience. However, the centralization pressures of mining exist in a large part due to latency of block propagation, as described in the following video. Compact blocks version 1 is not primarily designed to solve that problem.

https://www.youtube.com/embed/Y6kibPzbrIc

It is expected that miners will continue to use the Fast Relay Network until a lower-latency or more robust solution is developed. However improvements to the base p2p protocol will increase robustness in the case of FRN failure, and perhaps reduce the advantage of private relay networks, making them not worthwhile to run.

Furthermore, the experiments conducted and data collected using the first version of compact blocks will inform the design of the future improvements we expect to be more competitive with the FRN.

Who benefits from compact blocks?

-

Full node users who want to relay transactions but who have limited internet bandwidth. If you simply want to save the most bandwidth possible while still relaying blocks to peers, there is a

blocksonlymode already available starting in Bitcoin Core v0.12. Blocks-only mode only receives transactions when they’re included in a block, so there is no extra transaction overhead. -

The network as a whole. Decreasing block propagation times on the p2p network creates a healthier network with a better baseline relay security margin.

What is the timeline on coding, testing, reviewing and deploying compact block propagation?

The first version of compact blocks has been assigned BIP152, has a working implementation, and is being actively tested by the developer community.

- BIP152: https://github.com/bitcoin/bips/blob/master/bip-0152.mediawiki

- Reference implementation: https://github.com/bitcoin/bitcoin/pull/8068

How can this be adapted for even faster p2p relay?

Additional improvements to the compact block scheme can be made. These are related to RN-NG and are two-fold:

-

First, replace TCP transmission of block information with UDP transmission.

-

Second, handle dropped packets and pre-emptively send missing transaction data by using forward error correction (FEC) codes.

UDP transmission allows data to be sent by the server and digested by the client as fast as the path allows, without worrying about intermittent dropped packets. A client would rather receive packets out of order to construct the block as fast as possible but TCP does not allow this.

In order to deal with the dropped packets and receiving non-redundant block data from multiple servers, FEC codes will be employed. A FEC code is a method of transforming the original data into a redundant code, allowing lossless transmission as long as a certain percentage of packets arrive at its destination, where the required data is only slightly larger than the original size of the data.

This would allow a node to begin sending a block as soon as it receives them, and allow the recipients to reconstruct blocks being streamed from multiple peers simultaneously. All of this work continues to build on the compact blocks work already completed. This is a medium-term extension, and development is ongoing.

Is this idea new?

The idea of using bloom filters (such as those used in BIP37 filteredblocks) to more efficiently transmit blocks was proposed a number of years ago. It was also implemented by Pieter Wuille (sipa) in 2013 but he found the overhead made it slow down the transfer.

[#bitcoin-dev, public log (excerpts)]

[2013-12-27]

09:12 < sipa> TD: i'm working on bip37-based block propagation

[...]

10:27 < BlueMatt> sipa: bip37 doesnt really make sense for block download, no? why do you want the filtered merkle tree instead of just the hash list (since you know you want all txn anyway)

[...]

15:14 < sipa> BlueMatt: the overhead of bip37 for full match is something like 1 bit per transaction, plus maybe 20 bytes per block or so

15:14 < sipa> over just sending the txid list

[2013-12-28]

00:11 < sipa> BlueMatt: i have a ~working bip37 block download branch, but it's buggy and seems to miss blocks and is very slow

00:15 < sipa> BlueMatt: haven't investigated, but my guess is transactions that a peer assumes we have and doesn't send again

00:15 < sipa> while they already have expired from our relay pool

[...]

00:17 < sipa> if we need to ask for missing transactions, there is an extra roundtrip, which makes it likely slower than full block download for many connections

00:18 < BlueMatt> you also cant request missing txn since they are no longer in mempool [...]

00:21 < gmaxwell> sounds like we really do need a protocol extension for this.

[...] 00:23 < sipa> gmaxwell: i don't see how to do it without extra roundtrip

00:23 < BlueMatt> send a list of txn in your mempool (or bloom filter over them or whatever)!As was noted in the excerpt, simply extending the protocol to support sending individual transaction hashes for requesting transactions as well as individual transactions in blocks ended up allowing the compact blocks scheme to be much simpler, DoS-resistant, and more efficient.

Further reading resources

- https://people.xiph.org/~greg/efficient.block.xfer.txt

- https://people.xiph.org/~greg/lowlatency.block.xfer.txt

- https://people.xiph.org/~greg/weakblocks.txt

- https://people.xiph.org/~greg/mempool_sync_relay.txt

- https://en.bitcoin.it/wiki/User:Gmaxwell/block_network_coding

- http://diyhpl.us/~bryan/irc/bitcoin/block-propagation-links.2016-05-09.txt

- http://diyhpl.us/~bryan/irc/bitcoin/weak-blocks-links.2016-05-09.txt

- http://diyhpl.us/~bryan/irc/bitcoin/propagation-links.2016-05-09.txt