Schnorr Signatures

The replacement of Bitcoin’s digital signature algorithm (ECDSA) for the more efficient Schnorr algorithm has long been at the top of the wish list for many Bitcoin developers. A simple algorithm leveraging elliptic curve cryptography, Schnorr enables several improvements over the existing scheme all while preserving all of its features and security assumptions.

Notably, Schnorr signatures support “native multisig” which enables the aggregation of multiple signatures into a single one valid for the sum of the keys of their respective inputs. This functionality offers three important benefits:

-

Constant-size signatures irrespective of the number of participants in the multisig setup. A 50-of-50 transaction is effectively the same size as one that uses a single public key and signature. For this reason, the performance of such schemes is significantly improved by removing the original requirement of validating every signature individually. Additionally, the verification of Schnorr signatures is slightly faster than that of ECDSA.

-

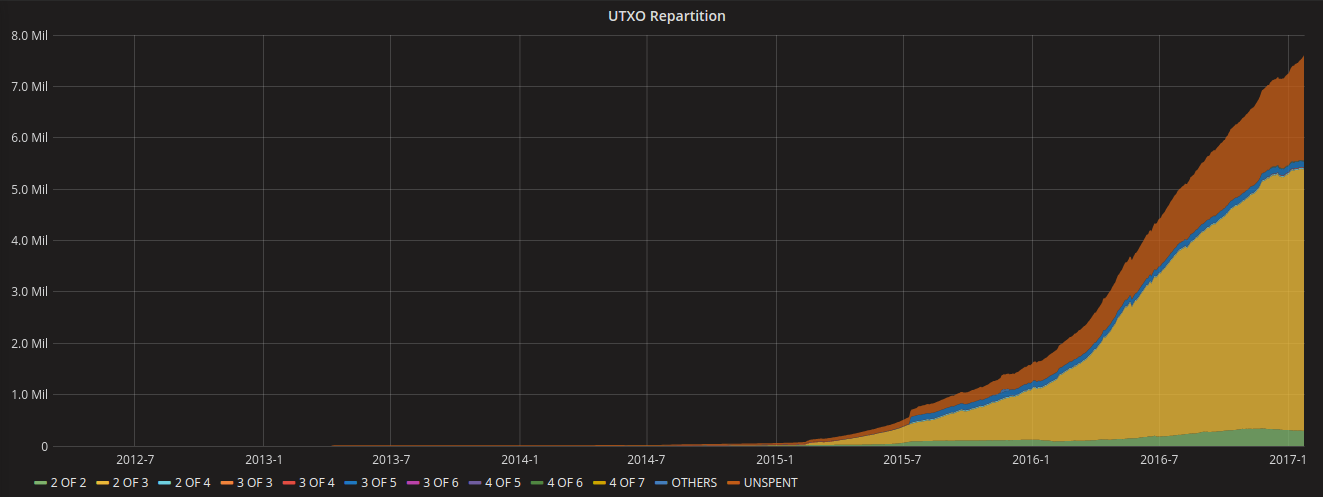

The diminished size of data to be validated and transmitted across the network also translates in interesting capacity gains. Considering the historical growth in the number of multisig transactions displayed below, the potential to reduce the size of these transactions is an enticing addition to existing scaling efforts. We should expect this trend to continue with the emergence and further adoption of payment channels.

-

From a privacy standpoint, Schnorr allows the entire policy of the multisig to be obscured and indistinguishable from a conventional single pubkey. In a threshold setup, it also becomes impossible for participants to reveal which of them authorized, or not, a transaction.

Distribution of unspent P2SH outputs according to their multisig setup. Source: p2sh.info

Unfortunately, unlike ECDSA, the Schnorr algorithm has not been standardized since its invention, likely because of the original patent enforced on it (which has since expired). While the general outlines of the system are mathematically sound, the lack of documentation and specification makes it more challenging to implement. Specifically, its application to the ephemeral keypairs design of Bitcoin involves security considerations that require further optimization.

The main challenge is defined by Pieter Wuille in his Scaling Bitcoin Milan presentation of Schnorr signatures as the “cancellation” problem. The possibility for a group of users to create a signature valid for the sum of their keys opens the door for an adversarial participant to subtract from the whole another user’s key. It essentially works like this:

Assume a 2-of-2 multisig scheme using input public keys Q1 and Q2. Rather than announce their key as Q2 to be combined with Q1, a malicious participant could provide, during the interaction phase, Q2-Q1 and effectively cancel out the other user’s key. Any fund sent to the joint public key is now only spendable by the owner of the Q2 key without the owner of Q1 even being aware of what is going on.

Fortunately, a solution is now available which involves multiplying every key used during the setup with a hash based on itself and all other keys involved before signing. This process is called delinearization. A proof of the security of this scheme is currently undergoing peer-review and will be formally described in an upcoming whitepaper.

In the near term, Schnorr signatures are being considered as viable replacement for two important functions of the Bitcoin protocol: OP_CHECKSIG & OP_CHECKMULTISIG.

The former is currently used to check ECDSA signatures against their respective public key according to the message in a transaction. By switching to an equivalent that checks for Schnorr signatures rather than ECDSA, the opcode can be used to authorize a spend requiring multiple signatures which would typically require calling OP_CHECKMULTISIG. Using a priori interaction not observable by the network, the collection of signers compute a combined public key along with a common signature which is verified by the new OP_CHECKSIG with the benefits of increased privacy and reduced costs.

The latter involves threshold scenarios where only n-of-m signatures are necessary to authorize a transaction. The current implementation of OP_CHECKMULTISIG validates all of the public keys and associated signatures required by the threshold policy. Because the computation scales linearly with the number of participants, Schnorr propose a much more efficient scheme which replaces the list of signatures with a single combined one along with a subset of the required pubkeys.

Until more evaluation of the delinearization scheme securing signers from malicious actors is performed, further applications of Schnorr signatures may be premature but the implementation of the features above can hopefully pave the way for a better understanding of the scheme in production. Contingent on additional peer-review, a BIP for the implementation of Schnorr Signatures could be proposed by the end of the year.

Signature aggregation

The properties of Schnorr allowing for the combination of multiple signatures over a single input are also applicable to the aggregation of multiple inputs for all transactions. Bitcoin developer Gregory Maxwell was the first to introduce the idea using insights from a previous proposal based on BLS signatures.

To properly understand the difference between this application and the ones described above it is necessary to consider how signatures are aggregated in each respective cases. In the native multisig setup, signers collaborate between themselves to compute a common public key and its associated signature. This interaction happens outside the protocol and only concerns the parties involved. The idea behind signature aggregation is to enable system validators ie. Bitcoin nodes to compute a single key and signature for every inputs of all transactions at the protocol level.

Because this scheme expands the scope of aggregation outside of the deterministic set of participants, it introduces a new vector of attack for malicious actors to leverage the “cancellation” bug. For this reason, the delinearization fix highlighted in the previous section is critical to the soundness of this method.

In terms of implementation, the proposal is rather straightforward: OP_CHECKSIG and OP_CHECKMULTISIG are modified so that they can stack public keys, delinearize them and once all associated inputs are validated, produce a combined signature for their respective transactions.

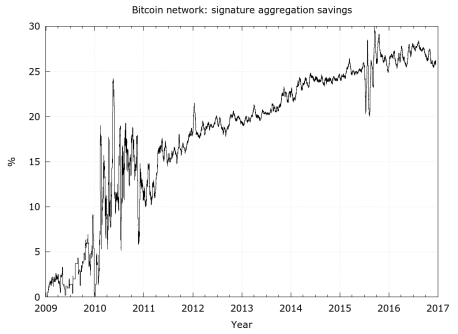

It is rather straightforward to evaluate the type of resources savings that would have been possible had signature aggregation been implemented since the genesis block. Assuming every historical signature would be reduced to 1 byte, except for one per transaction, analysis suggest the method would result in at least a 25% reduction in terms of storage and bandwidth. Increased used of n-of-n thresholds are likely to translate into more savings though they were not accounted for in this analysis.

Further information on Schnorr signatures

- Transcript of Pieter Wuille’s Scaling Bitcoin Milan presentation on Schnorr signatures

- Video of Pieter Wuille’s presentation

- Discussion about Schnorr Signatures at July 2016 Bitcoin developers & miners meet-up

- Schnorr documentation

- StackExchange - What are the implications of Schnorr?

- Elements Project: Schnorr Signature Validation

- SF Bitcoin Devs Seminar: Gregory Maxwell on Schnorr multi-signatures

- Bitcoin Core Developers meeting notes on Schnorr signatures